Article

The Gracchi Brothers

From Patricians and Plebeians to Nobles and Plebs

From the founding of the Republic in 509 BC, Roman society was divided into two class groups: the privileged patricians and the non-privileged plebeians. The patricians considered themselves the true Romans and stubbornly denied the plebeians civil rights: primarily access to public land (ager publicus) and the right to hold magistrate positions.

Paradoxically, it was the plebeians who formed the backbone of the Roman army, giving them leverage in political struggles. In 494 BC, during a military threat from the Aequi, Sabines, and Volsci, the plebeians staged their first secession—massively withdrawing to the Sacred Mountain, refusing to defend the Republic. This move forced the patricians to agree to the creation of the office of tribunes of the people with veto power, representing the interests of the plebeians.

In 451–450 BC, the plebeians achieved the codification of laws in the Laws of the Twelve Tables, which limited the judicial arbitrariness of the patricians. The next significant milestone was the reforms of 367 BC, initiated by tribunes Licinius and Sextius: the abolition of debt slavery, restrictions on patricians' use of public lands, and, most importantly, the admission of plebeians to the highest magistracy—the consulship.

With the adoption of the Lex Hortensia in 287 BC, the plebeians finally achieved legal equality with the patricians. This seemed to end the class conflict. However, a new internal conflict gradually emerged—this time social. The old patrician aristocracy was replaced by a new elite in the form of the most successful descendants of patricians and plebeians—the nobility. The "middle class" formed the equestrian order, while the lower classes became known as the plebs.

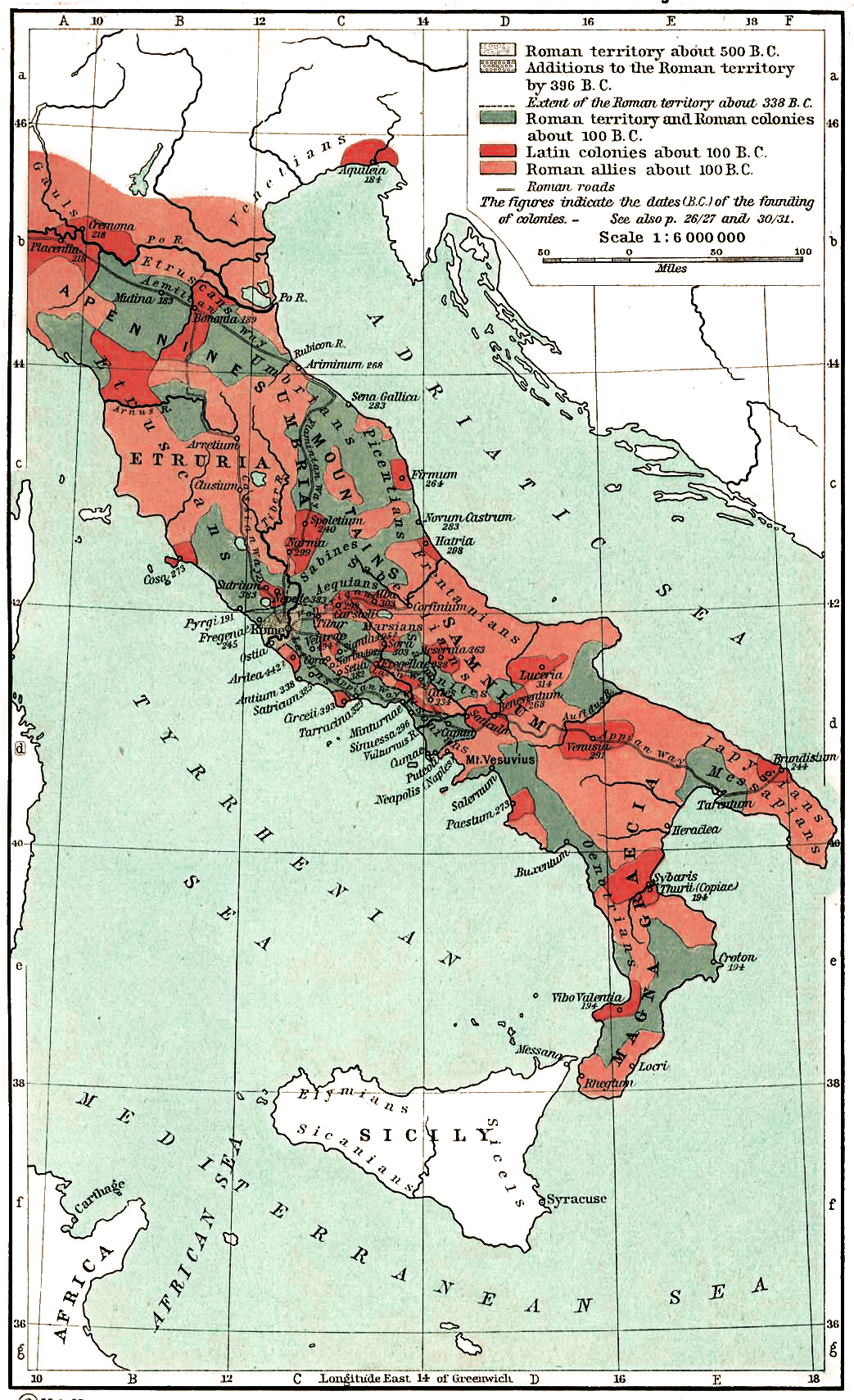

Meanwhile, the end of the acute phase of internal class struggle in Rome coincided with its external expansion. By the mid-3rd century BC, the Republic had subjugated all of Italy. Its cities and tribes had a certain degree of autonomy depending on the circumstances of their annexation to Rome, but the common feature for all Italians was the lack of Roman citizenship rights.

In 264 BC, Rome entered the most bloody conflict in its history—the Punic Wars for control over the entire Mediterranean. The epic victory over Carthage came at a great cost: as a result of the first two conflicts, the number of citizens halved from 292,000 to 143,000! However, after the victory, a flood of spoils and, above all, slaves poured into Rome. A disproportion arose: for every two free inhabitants of Italy, there was one slave. According to other data, the number of free inhabitants and slaves was equal.

The main flow of slaves naturally fell on the large latifundia of the nobles. Slaves actively replaced free people in agriculture, and the capture of fertile Sicily opened access to cheap commercial grain, allowing large landowners to switch to more profitable commercial production of wine, olives, fruit plants, and so on. As a result of free competition, the nobles ruined small landowners, who turned into proletarians (proles)—people who had nothing but offspring.

The impoverishment of small landowners negatively affected the state of the Republic's army, as it was recruited based on property qualifications, and each soldier had to equip himself at his own expense. Fewer and fewer citizens were subject to conscription, and those who did qualify still could not provide themselves with decent equipment.

Against the backdrop of property stratification, the nobles effectively turned the Republic into their own oligarchy. By the second half of the 2nd century BC, Rome once again found itself on the brink of an internal socio-political crisis.

The Youth of the Brothers

It was during this turbulent time that the brothers Tiberius and Gaius Sempronius Gracchus were born in 163 and 154 BC, respectively. Their family belonged to the upper echelons of the noble oligarchy: their father, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, was a two-time consul, and their mother, Cornelia, was the daughter of Hannibal's conqueror Scipio Africanus. The destroyer of Carthage, Scipio Aemilianus Africanus, was their cousin.

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus died in 150 BC. Cornelia rejected numerous marriage proposals and devoted herself to raising her children. According to Plutarch, "the brothers owed their excellent qualities more to their upbringing than to nature."

Having received an excellent education in the Greek manner, the brothers differed in character: Tiberius was calm, prudent, and restrained, while Gaius was hot-tempered and emotional. But according to Plutarch, the brothers had much in common: "As for courage in the face of the enemy, justice to subordinates, zeal for service, moderation in pleasures... they did not differ at all."

Thanks to the high social standing of the family and their upbringing, the brothers' public careers were predetermined. Tiberius, barely out of childhood, immediately received a position in the college of augurs—priests who interpreted the will of the gods by studying the flight of birds. Soon the Third Punic War (149–146 BC) began, and their cousin Scipio Aemilianus, who was also married to the Gracchi's sister Sempronia, took Tiberius with him on campaign.

Together with Scipio, he was able to see firsthand the degree of decay in the Roman army under "new historical conditions." The general had to virtually recreate the army entrusted to him to achieve final victory over Carthage. Around Scipio, a "circle" formed, whose members discussed Rome's problems and ways to overcome them: the moral decline of the nobility, the expansion of latifundia, the impoverishment of small landowners. It seems that the ideas of this "circle" greatly influenced the young Tiberius.

In 137 BC, as a quaestor, he went to the Numantine War in Spain. Under the city of Numantia, the Roman army suffered a crushing defeat, and only thanks to Tiberius's diplomatic skills did the Numantines spare the Romans and release them.

The defeat angered the Senate leaders, who even wanted to hand over the commander—Consul Gaius Hostilius Mancinus, along with his "officers" (including Tiberius)—to the enemy. This proposal was supported even by cousin Scipio, but Tiberius, thanks to his oratorical skills, convinced them to limit the punishment to the exile of the consul. After this, Scipio took command of the army, with Gaius Gracchus already serving under him, but it seems that after this incident, Tiberius became disillusioned with his cousin and decided to forge his own political path.

The Tribunate of Tiberius

At the end of 134 BC, Tiberius was elected tribune of the people and announced his intention to carry out agrarian reform in the interest of small landowners. He did not insist on new laws but decided to ensure the enforcement of the old Licinian-Sextian law of 367 BC, which limited the use of land by one person to 500 iugera (approximately 147 hectares), and with two sons, to 1,000 iugera. The excess was to be confiscated from large landowners for compensation and distributed among the poor citizens in plots of 30 iugera. Gracchus did not encroach on private property but only on public land (ager publicus).

The initiative led to a split in Roman society. The plebeians supported it, while the nobles, who controlled the Senate, were sharply opposed. Nevertheless, there were senators who supported Tiberius. These included Appius Claudius Pulcher (former consul of 143 BC), Publius Mucius Scaevola (current consul of 133 BC), Publius Licinius Crassus Mucianus (future consul of 131 BC), and Marcus Fulvius Flaccus (future consul of 125 BC). However, they were in the minority.

The senators planned to thwart the law through the veto of another tribune of the people—Octavius. Tiberius tried to win him over, and when that failed, he initiated an unprecedented procedure in the People's Assembly to remove the disloyal tribune and pass the law bypassing the Senate. An Agrarian Commission was created, consisting of Tiberius himself, his brother Gaius, and Appius Claudius Pulcher.

The Senate did not give up and, now in charge of the treasury, deliberately allocated little money for compensation for the confiscation of plots to paralyze the work of the Agrarian Commission. However, very timely for Tiberius, the ruler of Pergamum, Attalus, died, bequeathing his kingdom to the Senate and people of Rome. Tiberius and the People's Assembly seized the royal treasures from the Senate "for the benefit of the Roman people" and directed them to carry out the agrarian reform.

Tiberius's enemies continuously accused him of corruption, illegal appropriation of the Pergamene treasury, and aspirations for royal power. Only the tribune's immunity saved Tiberius from direct prosecution. According to tradition, re-election for a second term was only possible ten years after the first, but to continue the reforms, Tiberius intended to go against the established custom.

In the summer of 133 BC, Tiberius ran for a second term. Seeking to expand his social base, he announced plans to reduce the term of military service and grant Roman citizenship to the Italians. However, on election day, a crowd of Senate supporters, along with their clients, led by the Pontifex Maximus Scipio Nasica (former consul of 138 BC), came to the Capitoline Hill and beat to death the supporters of the reforms, including Tiberius himself. The Senate forbade the burial of the slain tribune of the people, and his body was thrown into the Tiber.

Nevertheless, to prevent a social explosion of the plebs, the Senate made concessions. Scipio Nasica was sent into exile in Pergamum, where he soon died in 132 BC. The Agrarian Commission was preserved: Tiberius's place in it was taken by Publius Licinius Crassus Mucianus, but the actual leader now became the younger brother, Gaius Gracchus.

At the head of the opponents of the reforms stood his cousin—the conqueror of Carthage, Scipio Aemilianus Africanus, in whose "circle" Tiberius had once absorbed ideas about reforming the Republic. However, Scipio found his relative's methods unacceptable, which seemed to violate all republican traditions—removal of unwanted magistrates, usurpation of Senate rights, and the attempt to run for tribune of the people for a second term. In the interest of preserving the Republic from tyranny, Scipio even approved the murder of his cousin.

In 129 BC, the Senate, on Scipio's initiative, transferred the resolution of agrarian disputes from the Agrarian Commission directly to Consul Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus, who was engaged in war in Illyria, thus effectively stalling the reform. However, in the same year, the conqueror of Carthage unexpectedly died. Rumors of his poisoning circulated.

The Tribunate of Gaius

In 126 BC, Gaius Gracchus was elected quaestor and then, as proquaestor (deputy quaestor in a separate province), went to Sardinia, where he participated in suppressing the uprising of local tribes. In winter conditions, the army lacked warm clothing. Then Commander Lucius Aurelius Orestes resorted to confiscations from loyal communities. They appealed to the Senate for protection, and it sided with the local population. The proconsul found himself in a disadvantageous position, but the proquaestor, thanks to his eloquence and his father's old connections, negotiated with the communities for the free supply of clothing to the troops.

The Senate was not pleased with the successes of the brother of the slain Tiberius. Seeking to keep Gaius out of Rome for as long as possible, the senators extended Orestes's powers as proconsul of Sardinia, so that Gaius could not legally leave the island, as he was obliged to perform the duties of proquaestor until the end of Orestes's term. Gaius spent the entire year 125 BC on Sardinia.

In the same year, a supporter of the Gracchi, Consul Marcus Fulvius Flaccus, proposed granting the Latins—the Italian tribes closest to the Romans—the rights of Roman citizenship, and the rest of the Italians the rights of Latin citizenship. The Senate rejected the law and assigned Flaccus to command the army in Transalpine Gaul.

Then the tribune of the people, Marcus Junius Pennus, proposed a law to expel all non-citizens from Rome, among whom were many supporters of the reforms. Gaius understood that his stay outside the capital could deal a heavy blow to his brother's cause. Although the Senate extended Orestes's proconsular powers for another year in 124 BC, Gaius returned to Rome on his own accord.

In the Eternal City, Gaius was greeted with enthusiasm. The Senate leaders did not intend to leave his unauthorized departure from the province unpunished, and Gaius was put on trial. However, Gaius brilliantly defended himself, pointing out to the jury that he had served in the army for twelve years instead of the required ten, and that his proquaestorship lasted two years instead of the mandatory one. The defendant did not forget to remind them of his exploits in Sardinia. As a result, Gaius was fully acquitted, and the trial only contributed to his growing popularity.

According to Appian, in December 124 BC, Gaius was "brilliantly" elected tribune of the people for 123 BC. In his speech before the People's Assembly, he demonstratively turned his face to the Forum, where the masses of the plebs stood, rather than to the Senate building. Thus, with a "light movement of the torso," Gaius clearly outlined the priorities of his policy. Upon taking office, he publicly accused the senators of his brother's murder and proposed a series of new laws:

On punishing magistrates who executed citizens without trial (an obvious revenge for his brother);

On prohibiting magistrates, who lost their positions by the will of the people, from holding new positions;

A new agrarian law that restored the work of Tiberius's commission;

A law to reduce bread prices for the urban poor, which also implied a public works program for building roads and warehouses, providing many free inhabitants of Italy with jobs;

A military law prohibiting the conscription of youths under 17 and introducing the provision of soldiers at the expense of the Republic;

A judicial law transferring extortion cases from the Senate to the equestrians;

A law under which taxes in the province of Asia were now collected by tax farmers from the equestrian order.

From the list of laws, it is clear that Gaius intended to rely on a broader social base than his slain brother—not only on the rural plebs but also on the urban plebs and the equestrians. This ensured the complete dominance of the "reform party" in the comitia, which constituted the People's Assembly. This time, Gaius was easily re-elected for a second term in 122 BC, and the Senate was afraid to interfere. Subsequently, in Soviet historiography of Antiquity, the tribunate of Gaius would even be seen as a "democratic dictatorship."

Gaius also proposed establishing new Roman colonies in Italy and, unexpectedly, in the defeated Carthage. The benefits of developing the North African coast were obvious, but the Senate did not hesitate to play the "Punic card" and began accusing Gracchus of treason and siding with the historical enemy.

At the same time, another tribune of the people, Marcus Livius Drusus, who sided with the Senate, proposed his own bills to abolish corporal punishment in the army and establish Roman colonies in Italy and Sicily. Thus, the Senate began to seize the reform agenda but without Gracchus's radicalism. In pursuit of retaining and expanding his social base, Gaius again proposed granting Roman citizenship to the Italians, but he did not have time to implement it.

Gaius was unable to be re-elected for the new year 121 BC. The new tribune, Marcus Minucius Rufus, proposed liquidating the colony in Carthage—Gracchus's favorite project. In a tense atmosphere between the rival parties in Rome, armed clashes began. During one of them, a consular lictor was accidentally killed, after which the Senate immediately issued an "emergency decree," granting Consul Lucius Opimius unlimited powers to restore order. Gaius, along with his supporters, attempted to fortify themselves on the Aventine Hill, but the consul, leading the army, forcibly drove them out. Defeated, Gaius Gracchus ordered his own slave to stab him.

The victorious Senate only dared to curtail the activities of the Agrarian Commission. Since the urban plebs represented the most active part of the electorate, and the equestrian order remained influential, the laws on bread, judicial, and tax reforms remained in force.

Among the people, a cult of the slain brothers formed. Sacrifices were made, and prayers were offered at the places of their deaths.

Conclusions

For the Senate and the nobility, the Gracchi brothers symbolized the violation of republican political virtues; they were seen as usurpers seeking unlimited tyrannical power through social populism. The viewpoint of Cicero is telling; in his treatise "On the Laws," he accuses Tiberius of depriving the rights of "honest men." In Cicero's eyes, Gaius unleashed civil war, "throwing daggers onto the Forum." Cicero fully justified the actions of the nobles in defending their noble Republic.

But there were alternative opinions that pointed out that the Gracchi's goal was not to deprive the Senate and the nobility of power but to alleviate the internal crisis and strengthen the Republic's military capability by restoring the prosperity of small landowners. Appian noted: "Gracchus's goal was not to create prosperity for the poor, but to obtain a combat-ready force for the Republic in their person."

Ironically, the Gracchi, with their reputation as radical reformers and almost revolutionaries, appear in this interpretation as conservatives, as their program sought to roll back the Republic to the first half of the 3rd century BC, when patricians and plebeians were already equal in rights, but the nobility had not yet established oligarchic rule. The victory of the Gracchi could have returned Rome to a classical polis system with high involvement of ordinary citizens as free landowners in the political process. Such a system did not imply professional military service for decades, so as not to detach citizens from the land. Such an army was unlikely to conquer distant countries, but it would not become a tool for the usurpation of power.

The Republic took a different path. A few decades later, Gaius Marius simply lowered the property qualification for legionaries and began recruiting proletarians, promising them land allotments in his name. Thus, instead of an army of free landowners with a republican consciousness, Rome acquired private armies of mercenaries loyal only to their commanders. In the 1st century BC, this led to a series of civil wars that ultimately buried the Republic.

Take the test on this topic

History

The Gracchi Brothers

We hope you were inspired by the story of the Gracchus brothers. Now test your knowledge about the Roman reformers!