Article

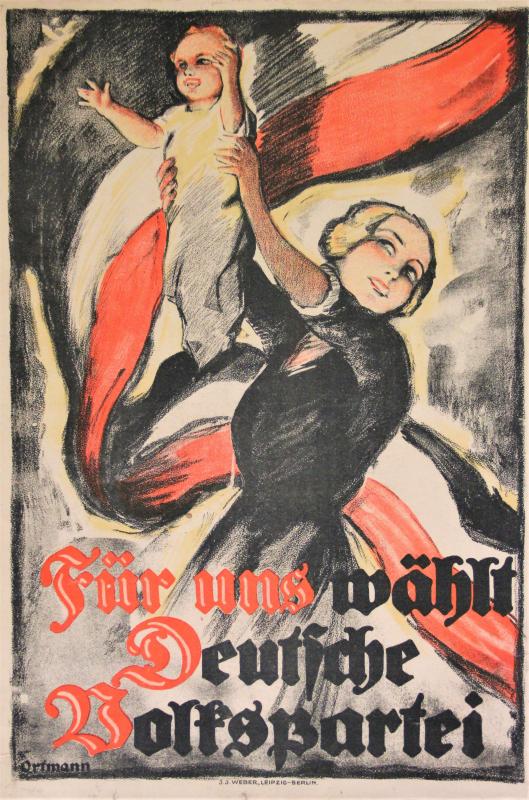

GERMAN PEOPLE'S PARTY (DEUTSCHE VOLKSPARTEI)

German liberalism as a political movement emerged after the Napoleonic Wars. Alongside the reform of domestic political institutions, German liberals also advocated the ideas of German nationalism and the creation of a unified German state. In fact, the words "nationalist" and "liberal" were synonymous at the time.

However, the revolution of 1848–1849 during the "Spring of Nations" clearly demonstrated the weakness of the liberal camp in Germany. The liberal all-German Frankfurt Parliament failed to become a real power, and all regional revolutions were eventually suppressed by the armies of the German monarchs.

Nevertheless, liberalism did not disappear, and liberals continued to sit in the parliaments of individual German states. However, the failure of the revolution posed a dilemma for them. If it was not possible to simultaneously create a liberal parliamentary unified German Empire, which of these two tasks should be prioritized—national unity or political liberalization? Different groups of liberals answered this question differently.

Some liberals chose to prioritize national unification, even if it meant doing so through the hands of the Prussian authoritarian military-bureaucratic regime. In the mid-1860s, the National Liberal Party was formed, becoming an ally of Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck in the unification of Germany. During the first ten years of the German Empire's existence, the national liberals were the largest faction in the Reichstag and Bismarck's support. In particular, they fully supported the "Kulturkampf" against Catholics and the "Exceptional Law" against socialists.

However, over time, the national liberals began to lose ground to Catholics, socialists, left liberals, and even conservatives. The decline was due to a narrow social base, the rise of more "mass" parties, and general disappointment with liberal economic policies, which led to the crisis of 1873 and the "Long Depression" at the end of the 19th century.

The electoral decline of the national liberals shifted them "to the right," making them increasingly loyal to the Kaiser regime and less tolerant of democratic reforms. They fully supported Germany's colonial expansion, and during World War I, they advocated for large-scale annexations following the expected victory of the Reich.

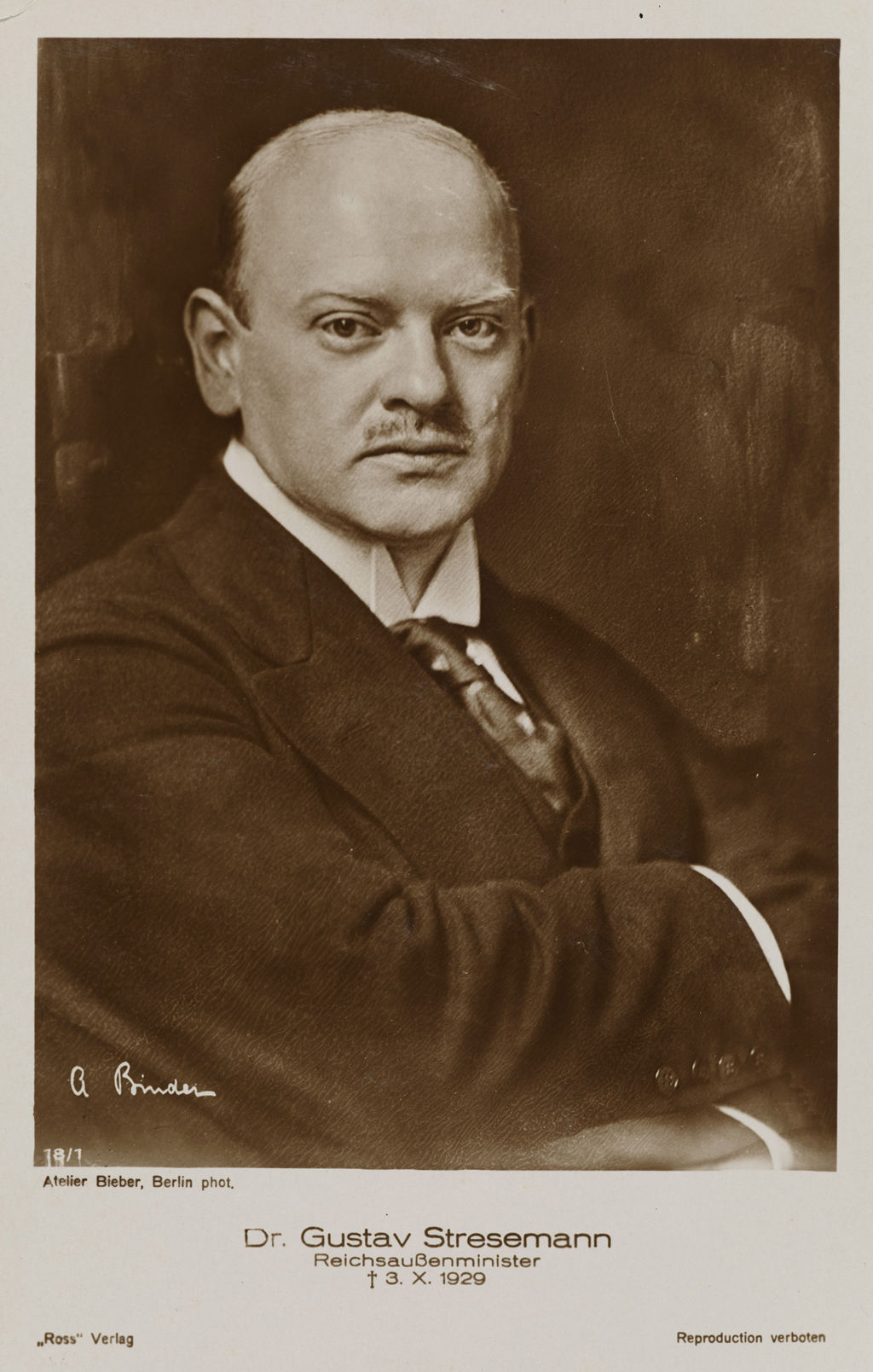

The national liberals reacted negatively to the November Revolution of 1918 and the overthrow of the monarchy. Immediately after the proclamation of the republic, a process of reassembling the liberal camp took place. Proposals were made to overcome the historical split and create a unified liberal party, but the perception of the new state system among liberals was so different that unification did not occur. The right wing of the national liberals moved to the conservatives, the left to the left-liberal German Democratic Party (DDP), and the core, led by Gustav Stresemann, formed the German People's Party (DVP).

In 1919, the party entered the Constituent Assembly, albeit with a modest result of 4.5%. It advocated for the restoration of a constitutional monarchy, great power status, and territorial integrity, thus the DVP voted against the Treaty of Versailles and against the Weimar Constitution.

In March 1920, during the unsuccessful Kapp Putsch by volunteer corps against the "Weimar Coalition" government, the party did not openly join the rebels but also did not oppose them in any way.

Opposition to the republic bore fruit in June 1920 when right-oriented voters became disillusioned with the ruling left-liberal DDP and shifted to the DVP. Those elections marked its electoral peak, with the party gaining 14% of the vote.

The social support of liberals, both right and left, consisted of employees, officials, academic workers, people in "free professions," traders, small and large property owners. In the latter case, the right-liberal DVP could particularly rely on industrialists from the coal mining and metallurgical sectors. These industries were interested in expanding government orders through the militarization of the economy and suppressing the labor movement for increased production. Until his death in 1924, the party's main sponsor was magnate Hugo Stinnes, who advocated for the establishment of an authoritarian dictatorial regime.

As for workers and peasants, the liberals had nothing to offer them. The unifying German liberalism also advocated for limiting the confessional autonomy of the Catholic Church. Thus, liberals reduced their appeal to Catholics and could mainly count on support only among Protestants.

Over time, the counter-revolutionary sentiment among right-wing liberals began to cool. The party leader Stresemann began to position himself as a "republican by reason" ("Vernuftrepublikaner")—a former monarchist who accepted the republic as a fact of political life and now sought to make it more acceptable to the right. In 1920, the DVP joined the Weimar coalition government along with the Center and left liberals. In 1923, Stresemann led the emergency "Grand Coalition" government for several months, which even included social democrats. Germany then faced hyperinflation, a diplomatic conflict with France and Belgium over the occupation of the Ruhr area, and right-wing and left-wing radical coups in individual German states. Stresemann's cabinet dealt with all challenges and saved the Weimar Republic.

The "Grand Coalition" collapsed by the end of the year, and Stresemann was forced to resign as Chancellor. However, he remained the head of the foreign ministry and achieved the normalization of Germany's relations with its former enemies. In 1924, the Dawes Plan was implemented—the United States began providing Germany with cheap loans, which were sufficient not only for reparations payments but also for developing domestic infrastructure. In 1925, the Locarno Treaties were signed, guaranteeing borders in Western Europe. The Entente began to withdraw its occupation forces from the left bank of the Rhine ahead of schedule. In 1926, Germany joined the League of Nations and immediately took a privileged position as a permanent member of the League Council. In the same year, Stresemann became a Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

The head of the DVP and foreign minister died of a stroke in October 1929, just weeks before the crash of the New York Stock Exchange, which marked the beginning of the Great Depression.

Even during Stresemann's lifetime, there was opposition within the DVP to his republican course. For example, large property owners in the coal mining and metallurgical industries reoriented towards more radical authoritarian conservatives. However, after Stresemann's death, anti-republican forces regained control of the party and once again advocated for the dismantling of Weimar in favor of a right-wing authoritarian regime.

However, this course did not help the DVP, which almost completely lost electoral support amid the economic crisis. From 9% in 1928, the party fell to 4.5% in 1930 and plummeted to 1–2% in 1932. Almost all former liberal voters shifted to the Nazis, who appeared as more active and socially-oriented defenders of the "middle class."

In 1932, the DVP supported the right-conservative authoritarian governments of Franz von Papen and Kurt von Schleicher. In the latter case, right and left liberals, with a combined support of 3% of the vote, were the only parliamentary support for the government in the Reichstag.

In March 1933, the few right-liberal deputies voted to grant Hitler's government extraordinary powers to issue laws bypassing the Reichstag. By July, the party was forced to dissolve itself.

Reasons for the ultimate failure of right-wing liberals in the Weimar Republic:

The split of the liberal camp into two parties;

A narrow social base limited to the Protestant "middle class";

During the Great Depression, the "middle class" reoriented towards radical populists from the NSDAP;

After the defeat of Nazism in 1945, the negative experience of the split in the liberal movement in the Weimar Republic was taken into account and overcome. However, the DVP had a reputation as an authoritarian and anti-republican party, so the revival of political liberalism in Germany occurred under the leadership of figures from the more democratic and republican DDP.

Take the test on this topic

History

German People's Party

Did you like the article? Now take the test and check your knowledge about the German People's Party!