Article

SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF GERMANY (SOZIALDEMOKRATISCHE PARTEI DEUTSCHLANDS)

The history of German social democracy began even before the creation of a unified German state. The theoretical foundations for the formation and subsequent activities of the labor movement were laid by the works of Karl Marx.

The first mass socialist organization was the "General German Workers' Association," created in 1863 by Ferdinand Lassalle. He rejected revolution and believed that socialism could be achieved through peaceful transformation by fighting for universal suffrage and winning elections. Moreover, Lassalle even allowed for an alliance between the working class and the Prussian authoritarian monarchy to jointly fight against the bourgeoisie and create a unified German national and social state.

Not all socialists liked Lassalle's program, and in 1869, orthodox Marxists August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht founded the Social Democratic Workers' Party in the Thuringian city of Eisenach, which focused on trade union struggle and the development of the cooperative movement. Moreover, unlike Lassalle, the "Eisenachers" were opposed to the forceful unification of Germany under the Prussian monarchy.

Nevertheless, despite the differences, both organizations targeted the same working audience, and by 1875 they merged into the Socialist Workers' Party.

The government saw a threat in the new movement, and by 1878 Chancellor Otto von Bismarck succeeded in passing the "Anti-Socialist Law," which banned the activities of any socialist organizations in the empire. Simultaneously, Bismarck began implementing social support measures to win over the working class and deprive socialists of mass support. Thus, old-age and disability pensions appeared in Germany, and a health insurance system was established.

However, Bismarck's policy proved unsuccessful. Despite the repression, socialists continued to be elected to the Reichstag as private individuals, and from election to election, more voters supported them. In 1890, the new Emperor Wilhelm II dismissed Bismarck, and the "Anti-Socialist Law" was repealed. The following year, the Socialist Workers' Party was finally renamed the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).

The 12-year underground period only united German socialists. A peculiar working-class subculture emerged – their own trade unions, sports associations, creative circles, and other clubs of interest. If desired, a conscious worker could live their entire life in a completely homogeneous socio-political environment.

During the reign of Wilhelm II, social democrats remained a legal political force that gradually increased its influence, and as a result of the 1912 elections, they received a relative majority of seats in the Reichstag. However, due to the Marxist nature of the party, the state power, conservatives, and even right-wing liberals still perceived socialists as the main threat to national security.

In August 1914, a sensation occurred. The overwhelming majority of German socialists supported Germany in the war that had begun and unanimously voted in parliament for war credits to the Kaiser’s government. From their point of view, the German Empire, with its limited parliamentarism and social security system, represented a "golden mean" between "reactionary" Russia and "bourgeois" England and France.

From 1914 to 1918, the SPD became an intermediary between the government and factory workers. However, while supporting the "defensive war," social democrats sharply opposed the annexationist plans and demanded peace based on mutual agreement. In the Reichstag, the SPD formed a coalition with the Catholic Center and the left-liberal Progressive Party, which demanded regime liberalization and democratic reforms.

Not all socialists supported the party leadership's course. A smaller part split into a separate Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD), which refused to support the government and advocated for a revolutionary transformation of society. The "Independent" social democrats welcomed the February and October revolutions in Russia but opposed active actions within Germany and preferred to wait for the "objective" historical process to lead Germany to revolution.

In turn, within the USPD itself, the "Spartacus" group formed, led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, who, on the contrary, believed that the revolutionary situation should not be waited for but brought closer. As a result, Liebknecht and Luxemburg were arrested and imprisoned.

In October 1918, liberalization of the regime began in the "Second Reich." The generals recognized Germany's hopeless situation and convinced the Kaiser to share power with the parliamentary majority. Firstly, this was supposed to soften the Entente, which actively used the slogan "war for world democracy." Secondly, the participation of civilian politicians in peace negotiations seemed to shift the responsibility for defeat from the generals. Social democrats entered the government for the first time and, together with their allies from the Center and the Progressive Party, gained the constitutional ability to dismiss chancellors with a vote of no confidence.

However, at the very beginning of November, liberalization got out of control. The naval command planned to send ships to sea and give a suicidal "last battle" to the English squadron, but the plan ended with a sailors' uprising in Kiel, which turned into a general November revolution. At the forefront of street demonstrations were activists from the USPD and the "Spartacus" group.

The SPD leadership reluctantly had to join the revolution to end it as soon as possible and return to constitutional order. The party leader and new chancellor, Friedrich Ebert, even advocated for the preservation of the monarchy, but his comrade Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed the German Republic on November 9 to appease the crowd in Berlin.

The first revolutionary government consisted of representatives from two socialist parties – the SPD and the USPD. However, their alliance was short-lived. The SPD advocated for a coalition with Catholics and liberals to lay the foundations of a democratic republic and only then begin a long parliamentary struggle for the evolutionary transformation of capitalist society into a socialist one. In contrast, the USPD believed that the moment for a socialist revolution had already arrived. As a result, at the end of December 1918, the "Independent" social democrats left the government. At the same time, Liebknecht and Luxemburg, released from prison, founded the Communist Party.

In January 1919, supporters of the Soviet Republic staged an uprising in Berlin, after which the social democratic Minister of Defense Gustav Noske began creating volunteer corps (Freikorps), recruiting there veterans, many of whom held right-wing radical views. They did not like social democrats, but "non-systemic leftists" seemed an even greater threat to them. The volunteer corps suppressed the January uprising and killed Liebknecht and Luxemburg without trial. In the following months, the same fate befell other Soviet republics in the rest of Germany, including Bremen and Bavaria. Thus, blood divided social democrats and communists.

As a result of the elections to the Constituent Assembly in January 1919, the SPD confirmed its status as the most popular party in the country – 38% of voters supported it. The Catholic Center party came second with 20%, and the left-liberal German Democratic Party came third with 18.5% of the votes. These three parties formed the ruling "Weimar Coalition," named after the city of Weimar in Thuringia, where the Constituent Assembly met.

In June, deputies from the three parties, after long debates, voted for the Treaty of Versailles, which all political forces in the country considered "unfair." For example, the SPD advocated for general disarmament, but it should have applied to everyone, not just Germany.

In July, a new republican Constitution was adopted, which established liberal political institutions and secured the right to private property. For the sake of preserving civil peace, the social democrats effectively postponed the implementation of their socialist program indefinitely. Nevertheless, the SPD managed to push through provisions such as the possibility of compulsory expropriation of property for public needs with compensation, state regulation of labor relations, the right of workers to create trade unions and works councils with the ability to control employers' actions.

From November 1918 to June 1920, SPD representatives headed the first republican cabinets, and out of the thirteen people who were heads of governments from November 1918 to January 1933, four were social democrats. In 1919, the Constituent Assembly elected party leader Friedrich Ebert as the country's first president. He held this post until his death in 1925.

Responsibility for the Treaty of Versailles negatively affected the reputation of social democrats among the right. By early 1920, the left-radical Soviet republics were suppressed, meaning the common threat no longer united the SPD and the volunteer corps. In March 1920, the Freikorps staged a putsch against the "Weimar Coalition" and briefly captured Berlin. The social democrats organized a general strike that paralyzed the actions of the rebels. The Kapp Putsch failed. However, since then, the SPD always had to consider the threat from both flanks of the political spectrum – the far left and the far right. The party became the main guardian of the centrist character of the new republic.

Due to compromise policies, some left-oriented voters became disillusioned with the SPD. Already in the next parliamentary elections in June 1920, the party fell from 38% to 22%. Almost all the disillusioned turned to the more left-wing USPD, which received 17.5%.

In turn, right-oriented voters became disillusioned with the SPD's "bourgeois" allies, who also lost many votes. The "Weimar Coalition" permanently lost its majority in the Reichstag and could no longer form governments without the participation of other parties. As a result, the Center and left liberals formed a coalition with the right-liberal German People's Party, which defended the interests of large industrialists. The SPD was not ready to join such a coalition. Nevertheless, it remained the most popular party in the country, and therefore right-centrist "minority governments" tried not to quarrel with it to avoid a vote of no confidence.

In 1920, the "Weimar Coalition" led by social democrats failed at the federal level, but in Prussia, which covered 60% of the country's territory and 60% of the population, the coalition continued to win and form governments until 1932. This was explained by the fact that most industrial centers and large cities, where workers lived who mostly voted for social democrats, were located here. For most of the Weimar period, the Prime Minister of Prussia was the social democrat Otto Braun, who, contrary to the opinion of many of his party members, did not allow the division of the largest German state. United Prussia was considered the electoral stronghold of the SPD and the citadel of the republican regime throughout Germany.

All the activities of social democrats in the Weimar Republic took place against the backdrop of internal debates about compromises with "bourgeois" parties and cooperation with radical socialists. For example, in September 1922, the SPD and USPD reunited, and this naturally shifted the party "to the left." Some regional branches of social democrats, for example, in Saxony and Thuringia, in October 1923, under conditions of hyperinflation and the threat of a right-wing putsch, allied with communists. In 1926, social democrats, together with communists, campaigned for participation in a referendum on the expropriation of property of former royal dynasties without compensation.

Another part of the party, primarily its leadership, was still inclined towards compromises with the "bourgeois" part of the political spectrum. From August to November 1923, at the peak of economic and political crises, the SPD even joined the "Grand Coalition" government led by right-liberal Chancellor Gustav Stresemann from the very German People's Party, which defended the interests of large entrepreneurs. At the same time, the imperial leadership of the party and the social democratic President Ebert sanctioned the introduction of troops into Saxony and Thuringia to forcibly break the coalitions of local regional branches of the SPD with communists. On May 1, 1929, the social democratic police of Berlin shot a communist demonstration, and in 1931, communists killed two capital police officers – members of the SPD.

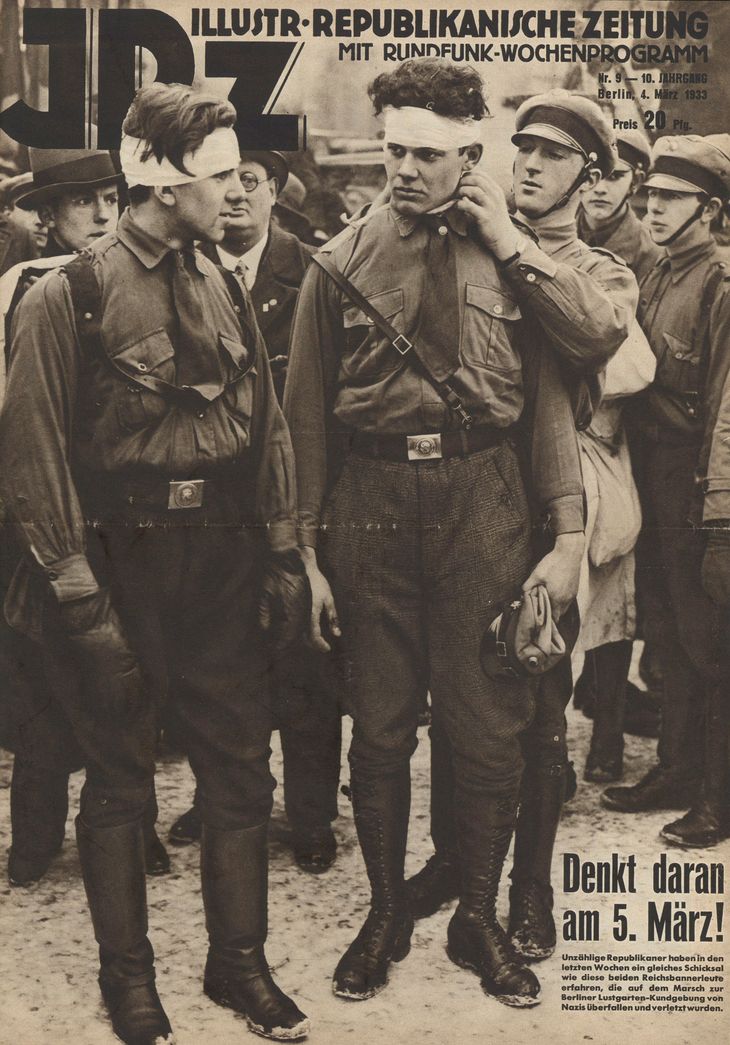

To protect the republic, social democrats, together with Catholics and left liberals, created the "Reichsbanner" organization in 1924. There was also a youth wing – the "Jungbanner." The total number of the "Reichsbanner" as a civil structure at its peak reached 3 million people, although the number of members of its paramilitary wing ("Schufo") did not exceed 250 thousand.

Social democrats returned to the "Grand Coalition" government and even led it after the 1928 elections, when the SPD received 30% of the votes. The party reaped the benefits of those few years when it was in opposition to right-centrist cabinets. By that time, the economic situation had improved, and radicalism had subsided.

This prosperity ended just two years later when Germany became one of the countries most affected by the Great Depression. The political crisis, which killed the republic a few years later, began due to the confrontation between the "right" and "left" wings of the SPD. In March 1930, the government led by social democratic Chancellor Hermann Müller proposed cutting unemployment benefits to save the budget. However, the SPD parliamentary faction voted against the initiative of its own chancellor, and he was forced to resign.

A new right-centrist government came to power, led by the Catholic Heinrich Brüning. Social democrats opposed his deflationary policy, which led to the dissolution of parliament and new elections in September 1930. The SPD's results fell from 30% to 24.5%, mainly in favor of the communists. These same elections were a triumph for the NSDAP, which gained more than 18% and became the second party in the country.

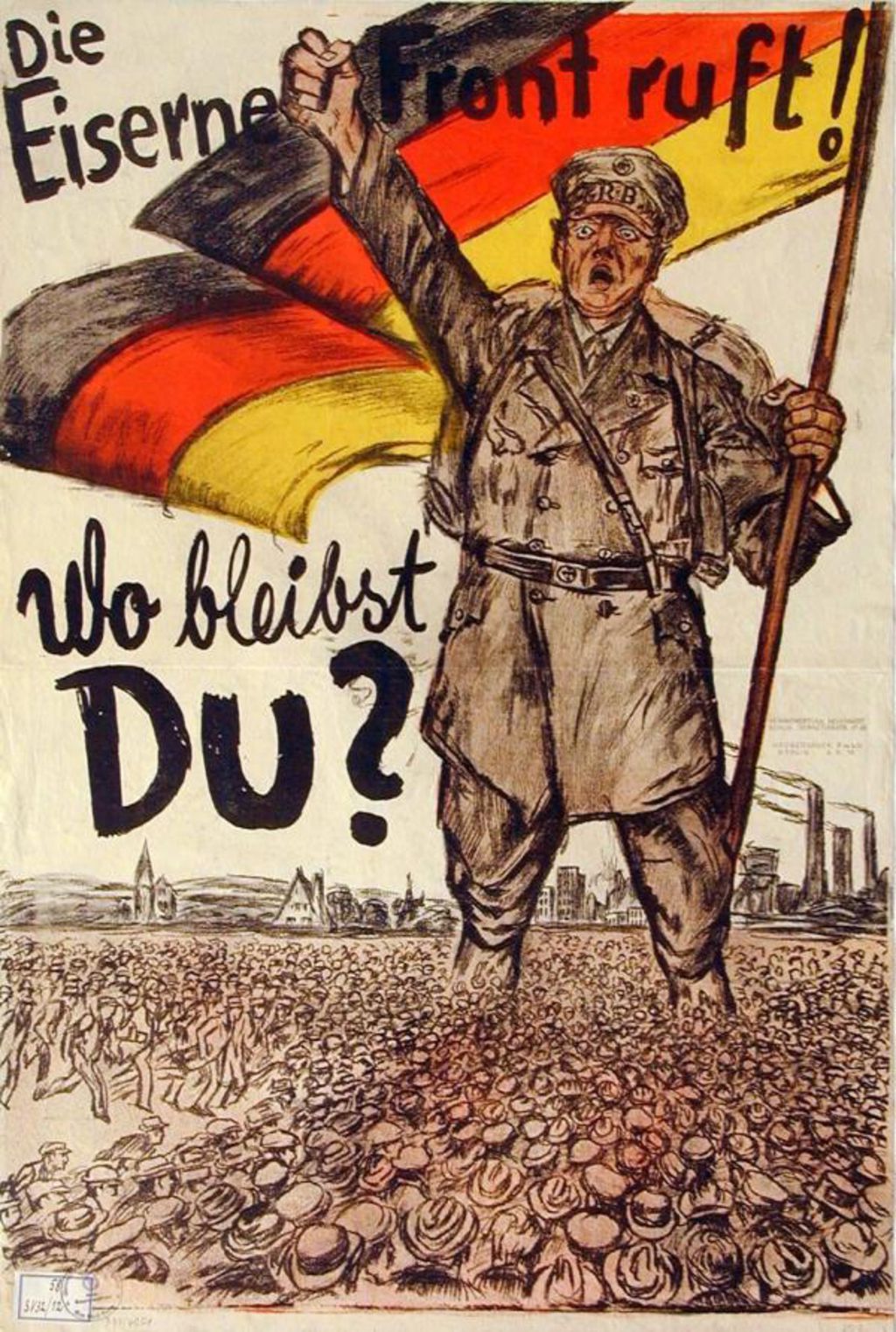

In 1931, the "Iron Front" emerged, which included the SPD, social democratic trade unions, the "Reichsbanner," and various workers' sports associations. The posters of the "Iron Front" featured three arrows symbolizing the fight against three main enemies – monarchists, Nazis, and communists.

Despite disagreements, centrist Brüning and social democrats did not go for a complete break, as the Center and SPD still had a joint "Weimar Coalition" in Prussia, where they together opposed the Nazis. In the spring of 1932, at the request of the chancellor, social democrats even supported the conservative President Paul von Hindenburg as the only candidate capable of defeating Hitler.

But by mid-year, the situation worsened sharply. In April, the Nazis won the Prussian Landtag elections, and the "Weimar Coalition" lost its parliamentary majority. However, the NSDAP could not form a cabinet alone, so the social democrat Braun remained head of the Prussian "minority government."

In May, as a result of intrigues, centrist Brüning resigned as chancellor, replaced by the non-partisan conservative Franz von Papen. He was already openly hostile to the SPD. In July, Papen convinced President Hindenburg to declare a state of emergency in Prussia and remove the "Weimar Coalition" government on the pretext that it was unable to control street clashes between Nazis and communists. On July 20, the Reichswehr occupied Prussian government institutions and dismissed Braun's cabinet. All power in the largest German state passed to the imperial government. The legal support for the Prussian coup was provided by the famous jurist Carl Schmitt, who advocated the priority of strong executive power with emergency powers.

Social democrats did not undertake any forceful actions. Armed resistance by the "Reichsbanner" and the Prussian police could have led to a civil war. A general strike by trade unions could have failed because, in conditions of mass unemployment, workers were unlikely to risk their jobs for political demands. Instead, the SPD filed a lawsuit against Papen in the Constitutional Court, which upheld the legality of the state of emergency and left everything as it was.

Indecisive conciliatory policies again collapsed the popularity of social democrats among the electorate, mainly in favor of the communists. In the July 1932 elections, the SPD fell to 21.5% and finally ceded to the Nazis the status of the most popular party in the country. The decline continued further – to 20.5% in November 1932 and to 18% in March 1933.

Having capitulated to Papen, the social democrats also capitulated to Hitler. In 1933, the SPD, trade unions, "Reichsbanner," and "Iron Front" were crushed without any armed resistance from their side. The most striking act of moral resistance can be considered the last opposition speech in the Reichstag, delivered by party leader Otto Wels on March 23, 1933, during the vote on granting Hitler's government emergency powers: "We can be deprived of freedom and even life, but not honor!". The SPD faction was the only one to vote against the Enabling Act. By June, the party was banned. Some of its leaders and activists went into exile, while others were arrested and sent to concentration camps.

Several reasons can be highlighted for the ultimate failure of social democrats in the Weimar Republic:

The SPD limited itself to "class" boundaries as a party for workers;

The reputation of a "revolutionary" Marxist party repelled the "middle class";

The reputation of an "anti-national" party responsible for the defeat in the war and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles alienated the "patriotic" electorate;

In 1920 and 1930, the party preferred to go into opposition rather than compromise principles and remain in government. This narrowed its opportunities for action;

In 1932 and 1933, the party capitulated to brute force and did not oppose it with its own brute force.

During the years of the Nazi dictatorship, those SPD functionaries and activists who did not go abroad were persecuted, and many were killed. There were social democratic underground resistance groups, and several well-known SPD figures (Julius Leber, Wilhelm Leuschner) participated in the July 20, 1944, plot against Hitler, for which they were executed.

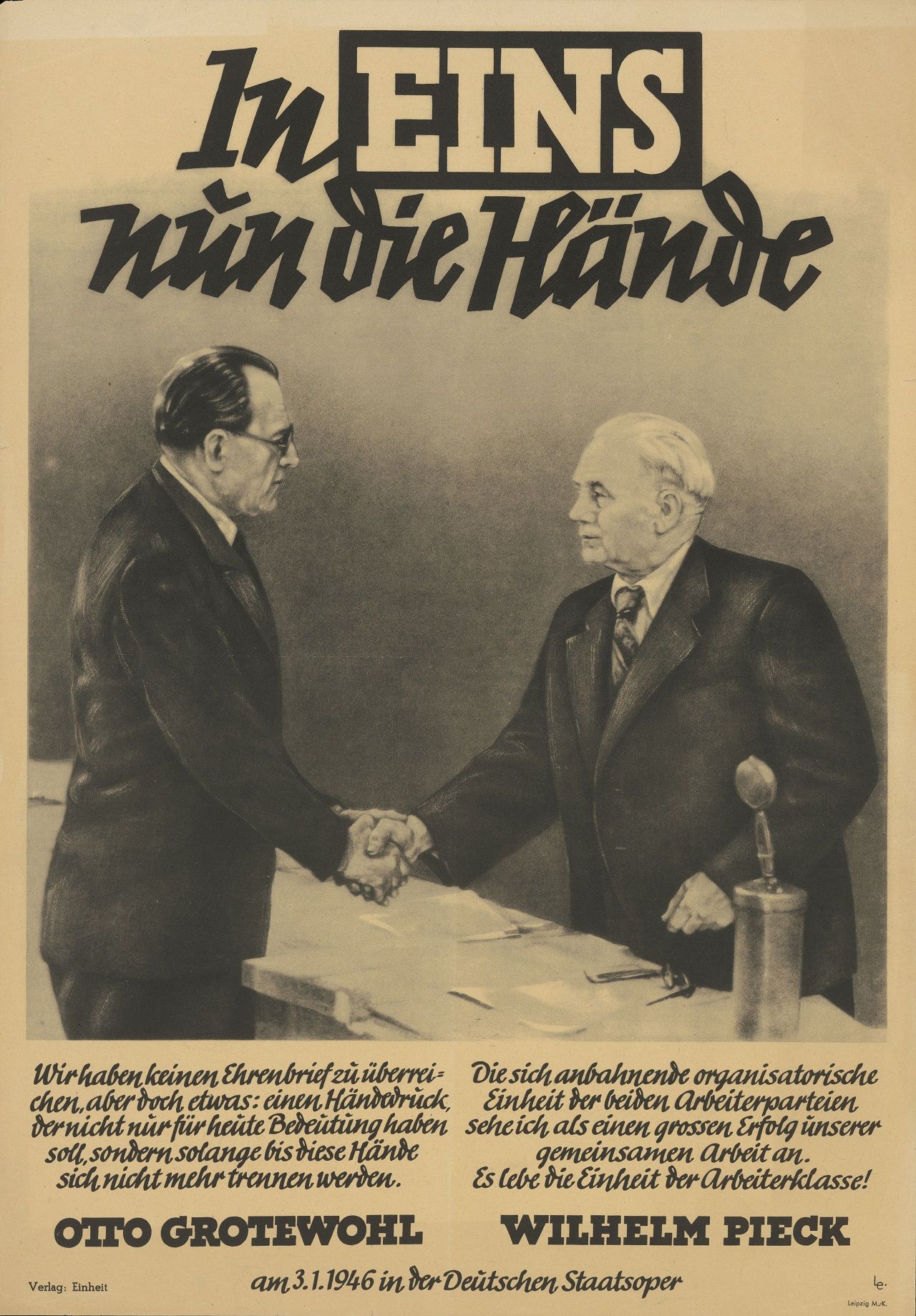

In 1945, the SPD was restored in both occupation zones. In the Soviet zone, an attempt was made to overcome the split in the socialist movement, and by 1946 local social democrats and communists merged into the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), which later became the ruling party of the GDR. Those social democrats who compromised with the communists took leading positions in the new state. For example, Otto Grotewohl became the first head of government of the GDR.

The Western SPD refused to cooperate with the communists. Instead, the party became a left-centrist pillar of the bipolar party system in the Federal Republic. The first head of the revived SPD in the West was Kurt Schumacher – a one-armed World War I veteran, Reichstag deputy, and Nazi concentration camp prisoner. Marxist Schumacher considered himself a German patriot and set about correcting the SPD's "anti-patriotic" reputation. From now on, the party positioned itself as a defender of national sovereignty, unlike the Christian Democrats of Konrad Adenauer, who sought to fully integrate into Western projects – NATO and the European Community.

The next generation of SPD leaders, led by Willy Brandt, revised the party's class character. In 1959, references to Marxism were removed from the party program, and the SPD was declared a "people's party." Its election results improved, and in 1966, social democrats entered the FRG government for the first time, and in 1969, Willy Brandt became the first social democratic chancellor of Germany in 39 years.

The Social Democratic Party remains one of the leading parties in the country to this day.

Take the test on this topic

History

Social Democratic Party of Germany

Did you like the article? Now take the test and check your knowledge about the German Social Democrats!